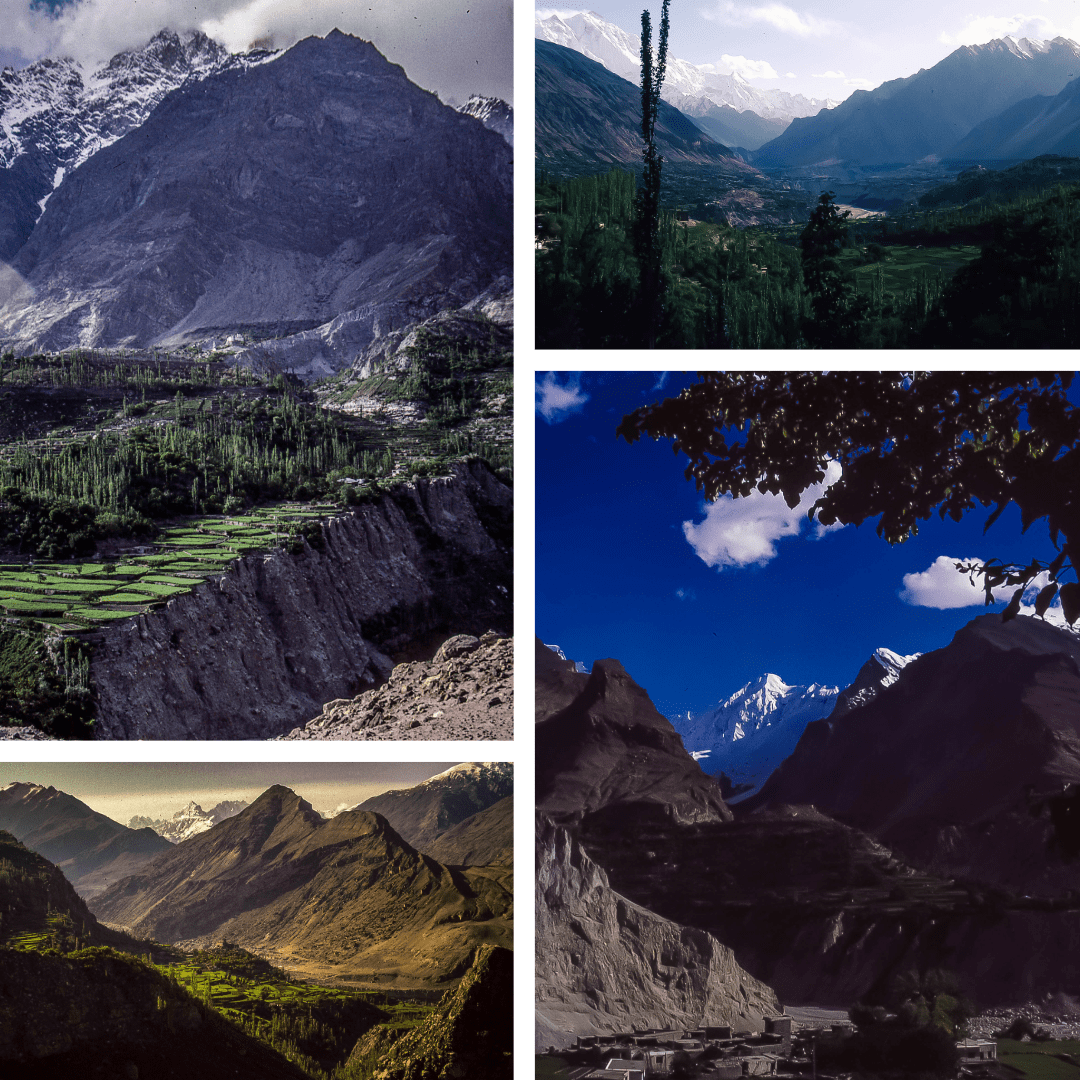

In the early 1980s, a journey through the Karakoram and Hindu Kush mountains was a voyage into the heart of mystery and wonder. Leaving the Uyghurs of the Chinese Turkestan behind, crossing Khunjerab Pass, the gateway into the heart of the mountain ranges of northern Pakistan and the fabled land of Hunza, one entered a world where tribal cultures converged.

Keeping Hunza as my base, I ventured up into the grandeur of lofty peaks, a portrait of rugged beauty, amazing moods and colors. I trekked to the snow line of Nanga Parbat, Rakaposhi, and to the impressive Baltoro glacier.

Also known as the Burusho of the Hunza Valley, the Hunza people live lives of remarkable longevity, having their health and vitality attributed to a diet rich in apricots, nuts and seeds and locally grown grains and vegetables. Against the backdrop of sharp peaks and glaciers, the Hunza people embodied the harmony between humanity and nature.

Away from the heart of Hunza, seemingly untouched by passaging time, beneath the surface a complex social fabric unfolded, where strictly defined gender roles and firearms were a constant reminder of the harsh realities of life in remote mountains. Being friendly and respectful was the key for a stranger to pass through their remote villages unharmed.

After exploring Hunza, instead of heading south to Gilgit and Baltistan, I continued west. Gilgit-Baltistan, a Shia-majority region of the otherwise Sunni-dominated rest of the country, suffered frequent bouts of sectarian violence in the 1980s.

Heading west into the heart of Hindu Kush was where many tribes and peoples mingled, creating a vibrant mosaic of traditions and customs. The route offered to explore the remote valleys of these mountain ranges, a crossroads of the Tajiks and the Wakhi of the Wakhan Corridor, the Nuristanis, the Pashtuns, and the Yidgha, the Kho, and the Kalasha of Chitral.

To reach Chitral from Hunza was a journey not without its challenges. The treacherous mountain roads cut through some of the world’s most rugged terrain, and tested the courage and resilience of the passengers; the drivers were in a league of their own having to navigate landslides and cross raging rivers. Only a handful of rough jeep tracks led west and anywhere near the Afghan border and the remote reaches of the Wakhan Corridor. The rough roads and sturdy jeeps were the lifeline connecting isolated communities to the outside world, albeit with frequent delays at river crossings, where stuck jeeps and pickup trucks were a common sight.

As I crossed Shandur Pass and the Upper Swat deep into the Hindu Kush, finally reaching the Chitral Valley, the landscape transformed, and the cultural tapestry took on new hues again.

My destination was the Kalash valleys of Bumburet, Rumbur and Birir, in the mountains beyond Chitral Bazar. Here, amidst stunning landscapes and surrounded by Sunnis (namely the Kho who are Sunni and Ismaili Muslims), the Kalash, the indigenous and original inhabitants of Chitral, thrived. Their unique culture, a polytheistic faith of animism, worship of ancestors and gods reminiscent of ancient Hinduism, survived through generations, with origins dating as far as 2nd century BC.

Some hundred years earlier, in the late 1890s, the Kalash culture extended to that of Kafiristan (a word that implies ‘Land of Infidels,’ coined by their Muslim neighbors) on the Afghan side of the border, whence in fact lie the Kalash cultural roots before they migrated to their present-day homeland. But that was until the people of Kafiristan finally adopted, or better, were forced to adopt Islam and discarded their ancient religion. Meanwhile, the Kalash have sustained their beliefs unaffected by that of their Sunni neighbors (unfortunately since 2015, the indigenous Kalash have been under violent threat by the militant Afghan Taliban, who routinely crossed into Chitral from Nuristan, stole their livestock and provoked the Sunni Kho to force the Kalash to convert to Islam, a pressure that has resulted in some forced conversions already).

From their distinctive house type of massive beams erected on steep hillsides, akin to that of Kafiristan villages of Nuristan, of interest to me and one of the key reasons I ventured into this remote region, and the decorative style of elaborate headdresses and garments worn by their women, the Kalash were a testament to the resilience of human spirit in the face of adversity of life in a remote region.

As the Kalash settlement pattern extended to the Afghan border, defined by the high ranges of the Hindu Kush, a new reality of life was at play in their isolated valleys. On the other side of the mountains, the Afghans fought the Soviets for four years then and the fight was nowhere in its end (continuing for six more years). Where I reached the last of the Kalash villages, Afghans came here to regroup and rest before returning across the border to fight the Soviets; this was three years before the CIA armed the Afghan mujahedin, the resistance militias, with the US-made Stinger anti-aircraft missiles. The Afghans I encountered in Bumburet valley then were friendly and proudly posed for my pictures.

Mine was more than just a physical odyssey—it was a voyage of discovery, a chance to witness the rich tapestry of cultures and landscapes that make this corner of the world unique. As I finally neared Peshawar, having traversed for days the landslide-broken road from Chitral, and I glimpsed a sign pointing west toward the Khyber Pass, the principal eastern gateway to Afghanistan and once part of the ancient Silk Road, I realized I was here before. It was ten years earlier. I passed through here twice, first time en route from Europe to India and then the second time on the way back almost a year later.

As I write this post, a memory of travels forty years ago, I can’t help but wonder what it would be like to travel all of those Karakoram and Hindu Kush mountain roads today. Although I know the roads have improved, though landslides continue, remembering well the ordeal it was to ride the rough roads atop jeeps with many locals and cargo, today I’d travel here only on an MTB or on a gravel bike. For the sheer beauty of these landscapes, if you are of the adventure spirit, do put Karakoram and Hindu Kush on your list!