Some 50 years ago, I developed a keen interest in the travels of the first western explorers that penetrated the Himalayas before WWII and in the 1950s. In the 1970s, I made several journeys into the Himalayas myself. I trekked extensively in Nepal Himalaya, Indian Himalaya, Sikkim and Bhutan, studying Himalayan architecture, namely house architecture, but also the architecture of Hindu and Buddhist temples and monasteries.

Subsequently, in the 1980s, I trekked around Tibet and traveled further into China and extensively in southeast Asia, the Philippine and the Indonesian archipelago. As I roamed about the Indonesian archipelago, from Sumatra to East Timor, and studied about headhunters, ikat design, symbols and heirlooms, and discovered that the early Indonesians, more accurately the Austronesians actually sailed as far as southeast Africa and Madagascar already around 500–700 CE, making them among the first to bridge Southeast Asia and East Africa across the Indian Ocean, I became so fascinate by their maritime capabilities that next my travels took me all over East Africa and to Madagascar itself.

While the 12th century saw significant cultural exchanges around the globe, it was not the initial point of contact or settlement for the Austronesians in Madagascar. Their 500–700 CE earlier arrival timeline aligns with linguistic, genetic, and archaeological data, underscoring the sophistication of Austronesian seafaring exploits and their undeniable pivotal role in shaping Madagascar’s cultural identity. They brought with them not only their language, which forms the basis of Malagasy today, but also agricultural techniques, namely rice cultivation, design of outrigger canoes, and distinctive cultural practices such as buffalo veneration and unique house design. It was when I trekked in the Madagascar highlands and came across the Zafimaniry house type that I first time wondered whether the house type and vernacular design solutions they practiced didn’t have a connection to the Himalayas.

Trekking throughout Nepal Himalaya in the 1970s, I became fascinated with the Himalayan house type. While the logic would have it, the concepts behind the Himalaya house design must have spread into the Himalaya from the Indian subcontinent, as I traveled more in Southeast Asia and noted the similarities with the house type throughout this diverse region, I pondered whether it was plausible the Himalaya house type crossed the Himalaya into Tibet and from there spread throughout southeast Asia, and eventually found its way to Madagascar.

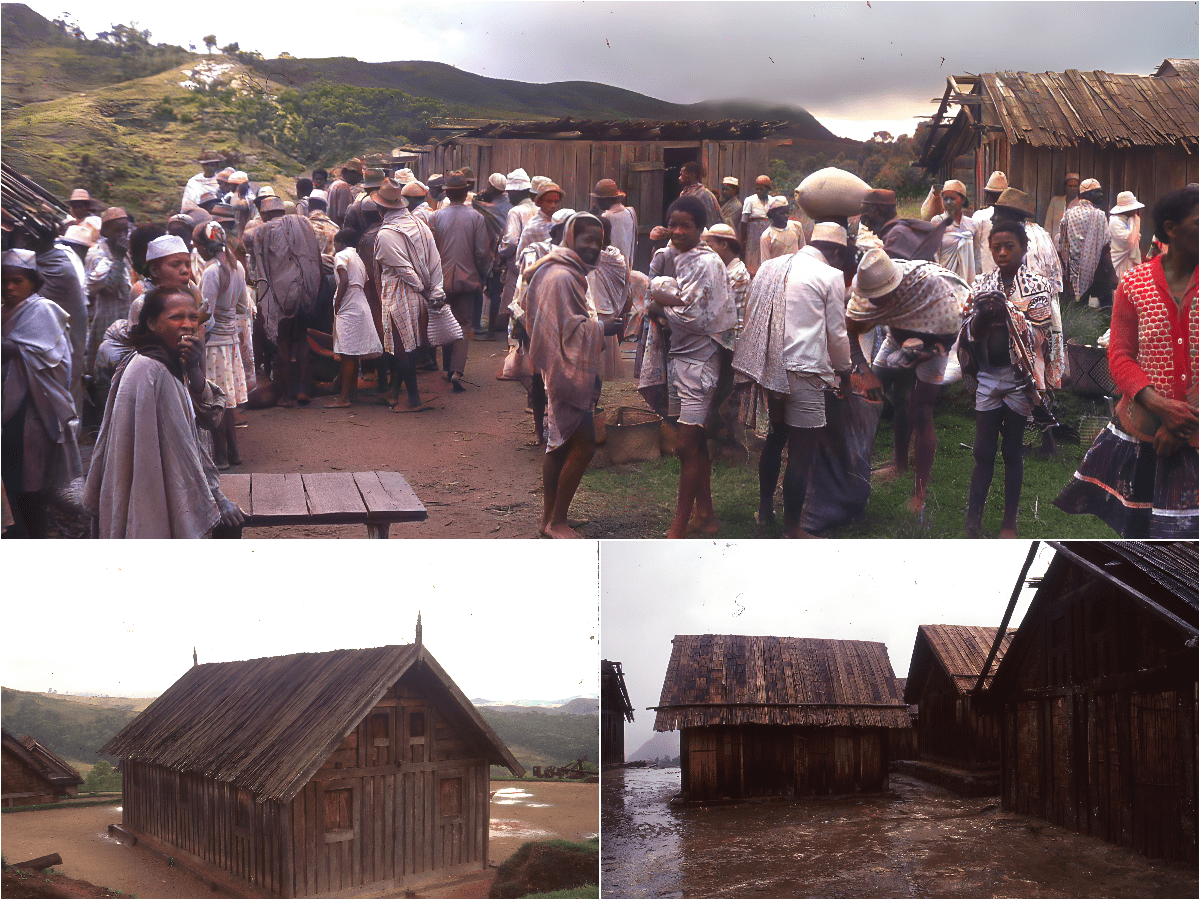

As I traveled around Madagascar in the mid-1980s, I could see that specifically the Zafimaniry people’s wooden houses were indeed reminiscent of Indonesian houses on stilts, even though I found this type of house in the Himalaya as well. That proved the ancient migration of the Austronesians clearly linked distant worlds long before modern globalization, and the roots whence they sailed from were somewhere throughout today’s Indonesian archipelago and elsewhere in southeast Asia.

But was it really that’s where their house design concepts originated from? Despite the clearly established link with the Austronesians, I was not convinced southeast Asia is where it all originated from. However, from the sources I reviewed, there is little explicit research directly tracing house type origins from the Himalayas to Southeast Asia, Indonesia, and Madagascar. Most academic discussions of architectural diffusion focus on Austronesian influences, starting from Southeast Asia and radiating outward through maritime trade and migration networks.

However, from my perspective, the roots of the Austronesian house type align with the anthropological view that Himalayan architecture too has unique symbolic and functional features (e.g., central hearths, spatial organization reflecting cosmology) that could have influenced neighboring regions as far as southeast Asia. While explicit scholarly confirmation of the Himalayan house type influencing Southeast Asia and Austronesian house design is none to my knowledge, the connection could be explored further by linking studies on early Himalayan domestic architecture with known Austronesian practices. Books like The Living House by Roxana Waterson discuss how Southeast Asian architecture embodies cosmological symbolism, which could share parallels with Himalayan traditions but stops short of specifying such connections as it focuses on the indigenous peoples of Southeast Asia.

My hypothesis might represent an original angle for interdisciplinary research. If so, my direct observations and travel experiences could inspire new academic exploration, perhaps indeed linking Himalayan architecture to broader cultural exchanges across Asia and the Indian Ocean.

But this kind of research is something I have no longer a sole interest in and time to pursue. This post merely inspired my coming across photographs from my travels among the Zafimaniry in the highlands of Madagascar 50 years ago. While my academic interests may not interest cyclists, and the Zafimaniry highlands do not figure anywhere to be an epic cycling destination, may this post inspire you to give Madagascar a closer look. Very few travelers actually go there, which is indeed a shame, as Madagascar is one of the truly fascinating outposts of the earth. That said, I must admit this memory I shared with you inspired me to ponder coming back to visit Madagascar, this time with my bicycle.