For fifteen years, I lived just below St. Mary’s Glacier, Colorado, at 11,000 feet (3,360 meters) above sea level. There were about fifty permanent residents here then, and a few more visited their cabins during summers. Winters were brutal at this elevation, and I usually traveled to Southeast Asia between November and May. Rest of the year, I cycled, hiked and worked out around my house at this elevation with no problems. But that was thirty years ago.

Over the years living in Colorado, I have climbed 23 fourteeners in Colorado, “almost” half of them (total is 53, by some accounts 58), and along with the 15 of the fourteeners in California, scattered across the state in three different mountain ranges (Cascades, White Mountains, and Sierra Nevada), these are the highest mountains in continental, aka contiguous, United States, meaning excluded Alaska.

Many years ago, I trekked as high as 20,000 feet (6,000 meters) in the Himalayas and felt just fine until about 18,000 feet. I bicycled across Bhutan, crossing several high passes, only a few years ago, and had no problem with altitude. A year ago in July, I tried to bicycle up Mt Evans (not my first time), a prominent 14,271-foot fourteener; that’s 4,350 meters high peak with a road right up to the summit. I made it up to 11,000 feet, feeling still good. Determined to ride higher and make it to the top, I felt the thin air from here on more and more. I took more breaks, gasping for air. At 12,000 feet, I felt miserable but pressed on higher to about 12,700 ft A.S.L. That was it. I couldn’t ride any higher; I just wasn’t getting enough oxygen. I had to turn around and started freewheeling back down.

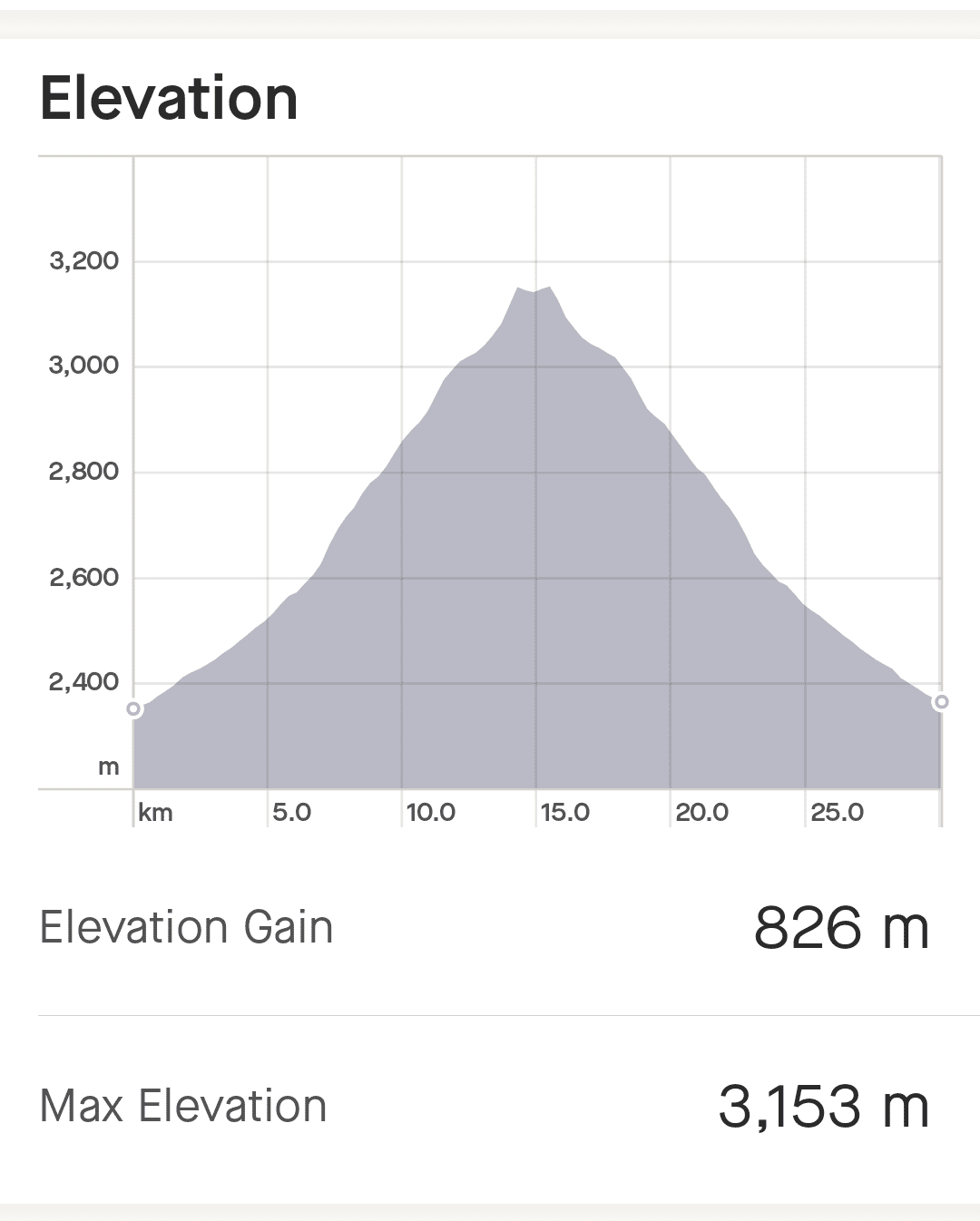

Last time I climbed a fourteener (with effort) was eight years ago. Recently, I bicycled into thin air four times. The first ride was up to 3,153 m (10,500 ft). I struggled as in the previous four months I have been cycling at a little higher than sea level. But I made it. A few days later, I rode up to 2,535 m (8,350 ft), another ride in the Front Range of the Rockies west of Denver. I felt much better but experienced the thin air on steep gradients, 6% and higher. Next ride took me to 2,217 m (7,300 ft) and I felt just fine as I did on the most recent ride up to 1,977 m (6,500 ft), a little higher than the elevation at which I ride around Denver, the Mile-High City (1,600 m, 5,280 ft). I rode the last four rides with my son, who is of course much younger and lives here continuously; he had no problems with the altitude and thin air on those rides at all.

My conclusion based on my experience is: with age, you just can’t hope to deal with the elevation as you did when you were younger. Some of my older (50+) friends from Denver when they came up to visit me at the glacier often felt the altitude and had to drive back down after just a couple of hours in my place.

It’s said Hillary, the first to summit Everest and who climbed many peaks in the Himalayas and the Karakoram over 7,000 and 8,000 meters, could not go higher than 12,000 feet when he was 60 years old.

Why with age (and I am older than the professed age of Hillary was when he had encountered problems with altitude), one just simply cannot feel good in higher elevations? It’s just a fact of life, aside from the obvious reasons:

Reduced physical activity: As people age, they tend to be less physically active. This can lead to a decrease in cardiovascular fitness, which can make it more difficult to adapt to the lower oxygen levels at high altitudes. I am not as active as I was when younger but I still ride and workout almost daily.

Underlying health conditions: Older adults are more likely to have underlying health conditions, such as heart disease, lung disease, and diabetes. These conditions can make it more difficult to tolerate the stress of high altitude. I have no health issues of the kind.

Changes in the body’s composition. As people age, their bodies lose muscle mass and gain fat mass. This change in body composition can make it more difficult to transport oxygen throughout the body. I am hardly fat, but still likely in this category.

It is important to note that even younger age is not a guarantee that everyone will be less likely to experience altitude sickness. There are many young people who are very fit and healthy, but still develop altitude sickness. Some people are simply more susceptible to altitude sickness than others. But with age, you definitely lose the ability to adjust to thin air and still perform physically as well as you do at your age in lower elevations.

It is possible that Hillary’s inability to go higher than 12,000 feet at 60 was because of a combination of factors, including his age, his reduced physical activity, and any underlying health conditions he may have had. It is also possible that he simply developed altitude sickness on that occasion.

To deal with thin air, all you can do is ascend gradually and allow your body time to adjust to the lower oxygen levels at high altitudes.

Stay hydrated, drink plenty of fluids to help your body transport oxygen.

Get enough rest. Don’t push it if you feel your body needs time to recover from the stress of high altitude.

Bottom line, if you develop any of the symptoms of altitude sickness, such as headache, nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, or dizziness, just turn around and descend to a lower altitude immediately.